Winner of the Run-off Poll and this September's Gallery!

The turtles! With over 200 million years worth of the hard shelled reptiles to draw upon (pun intended :P), from both the land and sea there should be no shortage of diversity this September!

The turtles! With over 200 million years worth of the hard shelled reptiles to draw upon (pun intended :P), from both the land and sea there should be no shortage of diversity this September!CIID 2011, results: "and the winner is... Davide Bonadonna!"

Yesterday, the museum of Lourinha has published the results of the last International Dinosaur Illustration Contest (7th edition).

The contest received 74 works by 29 artists of 10 different countries.

The winner was Davide Bonadonna, with his beautiful illustration of Diplodocus and Allosaurus!

This is another proof of Davide skills and, more generally, of the cleverness that all italian paleoartists use in this job.

In 2009 Davide won the third prize on the sixth edition of the same contest.

In 2010, he was prized with the Lanzendorf PaleoArt Prize in the scientific illustration category.

Davide was also the creator of the most important illustrations used in the "Dinosauri in Carne e Ossa" exhibition.

To view more illustrations of Davide, check out his website: www.davidebonadonna.com

CONFIDENCE

Unfortunately, the nature of confidence is that it blinds us to whether it is warranted or not.

Picasso's huge ego was an asset when it gave him the courage to break with a lot of traditions. On the other hand, Julien Schnabel's ego did him no favors when it led him to claim, "I'm the closest thing to Picasso that you'll see in this fucking life." Confidence can be the Jekyll or Hyde of art.

Artist Markus Lüpertz certainly had the confidence to stand up to his critics. When he erected his latest public artwork -- a creepy, 60 foot sculpture of Hercules with one arm, a big nose, blue hair and a stunted body-- the New York Times reported:

in the past his work has been, to put it kindly, misunderstood. One piece was smeared with paint and covered in feathers. Another was beaten with a hammer. Another was removed altogether after protesters demanded it be taken down. “It doesn’t matter,” said Mr. Lüpertz....“The general opinion of my art is that it is rejected. I attribute this to a lack of intelligence among the people.”

Some of Lupertz's confidence comes from avoiding nay-sayers:

I only work with students who admire me and think I am great. If I am not the one that takes their breath away, I don’t feel like working with them, because this would be a waste of time. It’s not about their individualism, it’s about my individualism. It’s not about their genius, it’s about my genius.Lupertz shows us that confidence can transform bad art into immense, unavoidable bad art.

At Stone Mountain, Georgia, sculptors Augustus Lukeman and Walter Hancock defaced an entire mountain with a sculpture the size of three football fields.

The sculpture, which depicts heroes of the Confederate Army, was sponsored by the Ku Klux Klan and the United Daughters of the Confederacy. As a work of art, it exemplifies the struggle between a pathetic lack of talent and disgusting racism. Most artists might look for a more inconspicuous location for such a struggle-- perhaps hidden in the back pages of a personal sketchbook. But if you have unquestioning confidence, you try to assert your position bigger and bolder and more permanently than anyone else's.

The jackhammer and dynamite are apparently favored tools of the overly confident. Consider this awful sculpture of chief Crazy Horse, currently on its way to becoming the largest sculpture in the world:

The sponsors of this statue hired sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski in 1948 to begin reshaping a mountain into a figure larger than Mount Rushmore. The head of Crazy Horse alone is 87 feet tall. The scale model pictured here in front of the despoiled mountain is so bad, an artist with any judgment would have returned to the drawing board. But confidence never heard the Turkish proverb, "No matter how far you've gone down the wrong road, turn back."

Confidence has served many artists well, giving them the strength necessary to undertake difficult projects and make bold decisions. Illustrator and art teacher Sterling Hundley reports,

I've had students in the past ask me the question: "Do you think that I am good enough?"This is surely true. On the other hand, when writer Flannery O'Connor was asked whether college writing programs were discouraging young writers, she responded "Not enough." This is surely true too.

My answer: "If anyone could say anything in that moment that would keep you from pursuing your dreams, then you should find something else to do with your life."

Distinguishing between helpful and unhelpful confidence is one of the greatest challenges facing any artist. When is it Jekyll and when is it Hyde? If there is a formula, I lack the confidence to articulate it here.

Guest Artist: Bryan Foote

Poetry: DRAGONSEED by Claire M. Jordan

Listen to the song of the world's wind

See my children leap up

See my children cast off

Soaring

Into the sky

Seek my seed - my children were born

Dancing

In a dazzle of colour

Now they spiral upwards

Climbing

Feathered with fractured light -

The light of the sun

Streams past the out-stretched hand

Shedding their teeth

To sow an army

Death and the fire of heaven

Cast them down

Shipwrecked in stone, still fringed

With frozen light -

Shall the stones take flight?

Listen to the song of the world's wind

See my children leap up

See my children cast off

Sorrow

Into the sky

Icarus fell, but Daedalus

Sweeps on - the storm

Could not out-pace him

Listen to me tell

How the same claws that grasped the ground

Clutched at the sundered sky

How the great beasts of thunder

With their bones of stone leapt up

And dwindled

Into bones of air

To glitter and shine

Listen to the song of the world's wind

See my children leap up

See my children cast off

Singing

Into the sky

Cauldron of changes

Feather on the bone

Circle of eternity

Heart in the stone

See my children leap up

Singing

Into the sky

[N.B. verse beginning "Cauldron of changes" is a traditional pagan chant which normally ends "Hole in the stone".]

Going Pro: Working with Palaeontologists (Flukes Part 5)

For my first Going Pro contribution I'm going to tie into my Flukes series of 2009 and 2010. While attempting to create a Shark Toothed Dolphin (Squalodon) for Dr. Ewan Fordyce (the tale of my efforts and MISTAKES can be followed in Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4) I picked up a few very good tactics and attitudes for getting yourself, as an artist, established with a working scientist. In the last couple of months I've gotten myself some more legitimate Palaeo-art gigs using these approaches with other palaeontologists here in Canada.

For my first Going Pro contribution I'm going to tie into my Flukes series of 2009 and 2010. While attempting to create a Shark Toothed Dolphin (Squalodon) for Dr. Ewan Fordyce (the tale of my efforts and MISTAKES can be followed in Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4) I picked up a few very good tactics and attitudes for getting yourself, as an artist, established with a working scientist. In the last couple of months I've gotten myself some more legitimate Palaeo-art gigs using these approaches with other palaeontologists here in Canada.

So I figured why not try to help everyone else out with my methods for all you aspiring and upcoming palaeo-artists to break into the palaeo-reconstruction field...

PART: 5

Working with (and for) Palaeontologists

Before I dive into this article, I'm going to clarify that the point of this article is for you to get gigs reconstructing critters for palaeontologists.

This is a very different task than what we usually get up to here on ART Evolved. Most often we are attempting to reconstruct something by ourselves for our own purposes. While you can certainly ask a scientists for their input in these effort, this is not the same as working on a legitimate reconstruction in my opinion.

Now before you get all enraged, I am not down playing independent palaeo-art, nor am I trying to insult people who create it. Hopefully everyone on this site knows how much "non-legit" palaeo-art I've created! When I use the word legitimate here I am solely referring to the fact the palaeo-art in question was commissioned by a scientist to accompany a formal publication. This to me means the artwork carries a bit more weight by having an outside authority's seal of approval and thus has had its own form of peer review.

Now with that quick preamble out of the way, how do you get yourself working for a palaeontologist in this way?

THE Attitude

I've found one's frame of mind toward palaeontology and their art that is the key to selling said art. To best illustrate this let me tell you a story...Just a few months ago, I met for the first time a new palaeontologist (Dr. Potential I shall dub them). I was very interested in pitching myself as a possible artist for Dr. Potential should they need a reconstruction done in their area of expertise (a big interest of mine). While they were willing to meet with me, I was stressed when almost immediately into our introduction Dr. Potential became very withdrawn and almost confrontational. I thought I'd done something offensive by mistake, but I pressed on in my usual manner of selling myself and my art (humbly casual). The interview didn't improve. In fact I thought I was crashing and burning when we got to my portfolio, and I was unable to answer some rather pointed technical questions about my anatomy choices in my pieces. I thought that was the end of the meeting, and I braced for the "thank you but no thank" you". Taking me by surprise Dr. Potential told me they were interested in me working for them. What I thought, after all that hostility?!?

It turns out Dr. Potential had tried collaborating with two other amateur artists in the past, and neither those experiences had been positive for the good doctor. In both cases Dr. Potential found the artists approached the subject matters like they were the experts, and began questioning or ignoring Dr. P's input and requests due to their own "research" of the topic subject matter. In the end Dr. Potential aborted both collaborations, and had a somewhat lowered opinion of "palaeo-enthusiasts".

I won over Dr. Potential with my very laid back and open approach to both my palaeo-art and the science in general. More to the point Dr. P very much liked the way that while I was well informed on palaeo, I didn't have a need to "flaunt it" or pretend I knew as much (or more!) than Dr. P (as I do not!). So that is how I got the gig.

So my first very key piece of advice when approaching a scientist to create palaeo-art for them is to forget everything you think you know about palaeontology. Especially about the topic you will be creating.

I don't mean to harp on people, but this is very important as a palaeo-artist. It doesn't matter how many museums you've visited or papers you've read, the scientist is the expert in the case of a legit reconstruction. That is why they are the ones writing the paper. Approach them as such. Do this and I guarantee you'll have luck.Besides you'd be surprised how much you can learn from talking to an expert (no matter how much or little reading you've done on their subject). Despite all the science that is out there in publication, I've always enjoyed direct conversations to learn about all that hasn't been published yet!

While attitude is key, there is another sticking point I've encountered over my ten or so pitches. How much your art costs. How you answer can really effect your efforts to getting established.

I venture the suggestion, at least while you don't have any formal credentials or portfolio full of commissioned work, you think about doing your first few pieces for free...

Immediately I should caution, I am not aiming to make my entire living or even a significant portion of it doing palaeo-art. I would just like to see my hobby pay for itself, and maybe see myself advance to the contemporary big leagues of the artform. As of such my not making money on my first few legitimate palaeo-art pieces is not a big lose to me.

This has me as a diametric opposite camp from the real artists out there. As a good example of their point of view I will call on our AE comrade Glendon's stance on the pay issue (I've run this by Glendon for the record). He suggests not doing any work for free. If you do there is a risk it will set up an expectation in your clients of this being the norm, and might even establish you a reputation as a "freebie" artist. While I agree with this on its fundamentals, legitimate professional level palaeo-art is very cut throat. You might need an edge in your rookie gigs.

I've lost over half my initial pitches to already established professional palaeo-artists this year, particularly Dinosaur reconstructions, as they offer some pretty stiff competition. For starters they have established relationships within the field, have a tested true body of work, and have demonstrated they have the methods to capture what the scientists are after. Who am I to compete with that right now, one on one, unless I level the playing field? "Selling" myself as the cheaper (to free) alternative has really been my only way to slip into circulation. The compensation in this case is building up my portfolio with actual published credentials.

I personally have "lost" a couple potential gigs (initially I was signed on a the tentative artist due to being free) when the project got money for a press release. Rather than risk paying a no name unestablished talent such as myself, they go to the proven stars when money enters the equation.

The other way I justify not making money off this art is that at moment I am not making any money creating non-legitimate palaeo-art, how could not being paid to actually create legitimate stuff hurt anymore?

Working for free is just one strategy, and it has been working for me off and on this year. Take what you may from it. The payoff is I have a potential half dozen reconstructions in the works now (one possibly paying!). Of course I'm at the whim of marketing and communication departments for the majority of them, especially should money for a formal press kit come up with a project. So mine is not the most stable strategy. Mind you I'd venture there is no such thing in the palaeo-art game...

The Benefits

So what are the payoffs of doing your art for free while defaulting on all your prehistoric know how? Quite a few actually. Not only for your art but also your knowledge in the field of palaeontology.

Here are just some of the benefits I encountered working with Dr. Fordyce in New Zealand.

Access to totally brand new specimens. This one was huge. When working with scientists you often get a sneak preview of things no one else in the palaeo community has ever seen. While you typically aren't allowed to talk about them (at least if you want to keep your name good in the field) there is something extremely satisfying about getting to be one of the first to see a new prehistoric critter. Plus if you're really lucky you could find yourself to be the first person to ever reconstruct it!

Access to totally brand new specimens. This one was huge. When working with scientists you often get a sneak preview of things no one else in the palaeo community has ever seen. While you typically aren't allowed to talk about them (at least if you want to keep your name good in the field) there is something extremely satisfying about getting to be one of the first to see a new prehistoric critter. Plus if you're really lucky you could find yourself to be the first person to ever reconstruct it!

When working with a palaeontologist often a lot of this guesswork (or outright conjecture) can be taken out of the picture. Every palaeontologist I've talked to is sitting on some knowledge of these details, either not published yet or that they know of from obscure references you don't know about (they are paid to know this stuff). Working with them, you'll find suddenly your work can become the cutting edge reconstruction of the critter in question by including things previous reconstructions lacked!

You'll become a part of the research process. One of the other cool byproducts of working with a palaeontologist on a reconstruction is that your seeking as much information about a fossil as a living animal can spur new insights or areas of inquiry about them.

You'll become a part of the research process. One of the other cool byproducts of working with a palaeontologist on a reconstruction is that your seeking as much information about a fossil as a living animal can spur new insights or areas of inquiry about them.

While working with Dr. Fordyce, a quick question I had about the placement about fins on the Shark Toothed Dolphin suddenly caused him to consider every other reconstruction of these animals previously made. He realized based on his own recent work on dissecting modern Dolphins that all previous reconstructions (and even most museum mounts of Dolphin skeletons both fossil AND modern) were wrong in the angle they were placing the ribs. Meaning not only was my reconstruction going to be the first to represent this cutting edge idea, but that I'd accidentally spurred it into entering the equation. Direct feedback and input. The most rewarding and unique result of collaborating with a scientist is getting a qualified opinion on your reconstruction. While there is nothing wrong with feedback from palaeo people like those here on ART Evolved (seriously love you guys for it all!), this doesn't quite compare to getting it from one of the top minds on the subject. Especially when you finally nail the critter, and get the experts seal of approval!!!

Direct feedback and input. The most rewarding and unique result of collaborating with a scientist is getting a qualified opinion on your reconstruction. While there is nothing wrong with feedback from palaeo people like those here on ART Evolved (seriously love you guys for it all!), this doesn't quite compare to getting it from one of the top minds on the subject. Especially when you finally nail the critter, and get the experts seal of approval!!!

So I hope this random ramble is of some use to you. While I'm by no means a professional or big name in the field of palaeo-art, using these steps I've definitely made headway to at least breaking into the scene later this year. I hope that one day you'll have the same luck as me!

Dinosaurs on DrawBridge

This is a heads up from Simon Fraser, comic book artist and a contributor to the cooperative art blog DrawBridge, who wants to share some wonderful dinosaur art.

Check out the dinosaurs on DrawBridge, I dare you not to smile!

September Run Off Vote

As the themes in question don't really complement each other all that well (apart from all being armoured) we're having a run off vote to decide the final theme of the gallery.

So please vote on the new run off poll located on our right sidebar. Though this time you can only vote for one choice...

THE ERA OF CELEBRITY ILLUSTRATORS

|

| From the back cover of Life Magazine. When was the last time you saw an ad like this? |

Magazines urged readers to spend more time studying illustrations:

This was all driven by economics, of course. The general public followed the work of top illustrators and made purchasing decisions based on their art:

|

This was the great power of stationary images in an era before people learned that pictures could also be made to move and talk.

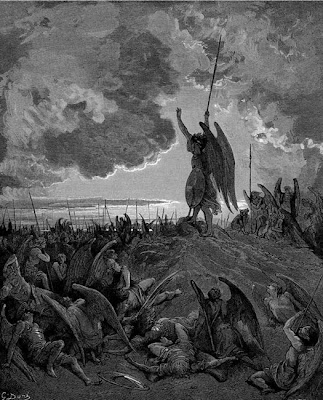

Like the Cecile B. DeMille of his day, Gustave Dore (1832-1883) shaped the world's image of epic stories such as the Bible, Paradise Lost and Dante's Divine Comedy. His books (and his visions) were everywhere.

Celebrity illustrators were were richly paid for their contribution to the mass entertainment industry. Charles Dana Gibson, who created the popular Gibson Girl, went from being a cartoonist for Life Magazine to taking over the entire magazine. His work enabled him to retire to his own private 700 acre island. Illustrator Henry Raleigh earned enough from drawing illustrations for three or four months to spend the balance of the year traveling the world lavishly with family and friends. He spent freely, giving away thousands of dollars. He maintained a yacht, owned a mansion and kept a large studio in downtown Manhattan.

Those days are gone. Like a huge peristaltic wave, the mass entertainment market has moved beyond illustration to other media.

There is nothing surprising about this. The golden age of illustration began in the 19th century by crushing the old fashioned wood engraving industry, which could no longer retain an audience when compared to color photo-engraving. Later, silent movies could not hold out for long against sound movies. Black and white movies were similarly vanquished by color movies. It remains to be seen what will happen with 3D, or 48 frame per second movies, or the next development after that.

This evolution seems to be powered primarily by the economics of mass marketing. There will always be a significant role for still pictures, but a medium that talks (and therefore doesn't require the consumer to read text), that moves (and therefore doesn't require the consumer to imagine the implications of a moment isolated by a static drawing), a medium that completely fills our sight, sound, olfactory and other senses, allowing us to passively absorb, seems to have a natural advantage over a medium that doesn't fill in all the blanks for us.

I see no prospect of this trend reversing itself, barring a global electromagnetic pulse (EMP) from thermonuclear war that renders all electronic viewing devices useless. If nuclear winter ever comes, illustrators can look forward to returning to their historic birthright as the powerful shamans who make magic images on the cave walls.

But for now, I think it is important to emphasize that, while illustration is no longer the centerpiece of the entertainment world, and the great peristaltic wave took celebrityhood and money with it, it did leave the "art" portion behind. And that, my friends, is the most important part.

Convergent Blog

IS IT OKAY TO LIKE PULP ART?

Last week the Society of Illustrators opened a wonderful exhibition of pulp magazine covers from the 1930s and 40s. The show includes nearly 90 paintings of scantily clad damsels in distress, hooded fiends with elaborate torture devices, and futuristic space heroes. This is probably the most emotionally uncomplicated art you will ever find: big, juicy paintings with the open heart (and emotional maturity) of a 14 year old boy.

But most of these pictures are painted with a technique as vulgar as their content. There was no room for subtle colors and elaborate compositions on a magazine rack crowded with competing pulp magazines.

Young male readers were tantalized by the prospect of what lay beyond those slightly parted dressing gowns or those strategically torn shirts. They pored over these illustrations for clues to what awaited them someday. It's a mark of their innocence that their best plan for winning such favors was by rescuing a girl from space monsters.

If you're looking for a holiday from moral complexity, pulp art may be just the oasis for you. In fact, the owner of this marvelous collection, Robert Lesser, calls it “escape” art. But its simple mindedness is the source of both its joyful strength and its gnawing weakness.

Let's put aside that this stuff is politicallly incorrect. My question is focused solely on artistic merit. Is this stuff anything more than “chewing gum for the eyes”? What are we to make of art that is not particularly well painted and does not challenge us mentally or emotionally, that raises no questions and doesn't expand our vision, but is undeniably likable for nostalgic reasons?

Beryl Markham cautioned us about the temptation to look over our shoulder at simpler, bygone days:

Never turn back and never believe that an hour you remember is a better hour.... Passed years seem safe ones, vanquished ones, while the future lives in a cloud, formidable from a distance. The cloud clears as you enter it. I have learned this, but like everyone I learned it late.

The fact that such ethical clarity is an illusion doesn’t mean it isn't art.

Know When To Fold 'Em

Both papers, however, present geometric data that can come across as a bit inaccessible for your average artist, so I'm going to try to break down their conclusions for those of us who are more visual thinkers. The Sullivan paper, in particular, discusses the degree to which the wrist could fold, but doesn't necessarily provide diagrams or even final angle between the metacarpals and ulna for each species that could be used as a simple reference. I've done my best to translate their findings into the image at the top of this post, using modified skeletal diagrams by Scott Hartman and Jaime Headden.

* Sullivan, C., Hone, D.W.E., Xu, X. and Zhang, F. (2010). "The asymmetry of the carpal joint and the evolution of wing folding in maniraptoran theropod dinosaurs." Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 277(1690): 2027–2033.

Sketchbooks - why?

Sketchbooks are an essential part of any artist's or designers and I've just posted a few thoughts on their use over at Paleo Illustrata arguing why in our age of technological wonders the humble pencil and sketchbook is still the best method of getting your ideas down quickly and with minimum fuss. Not only that, but other reasons too - head on over and take a look.

Blog Archive

-

▼

2011

(265)

-

▼

June

(14)

- House of God (Application to the Department of Cit...

- Winner of the Run-off Poll and this September's Ga...

- CIID 2011, results: "and the winner is... Davide B...

- CONFIDENCE

- Guest Artist: Bryan Foote

- Poetry: DRAGONSEED by Claire M. Jordan

- Going Pro: Working with Palaeontologists (Flukes P...

- Dinosaurs on DrawBridge

- September Run Off Vote

- THE ERA OF CELEBRITY ILLUSTRATORS

- Convergent Blog

- IS IT OKAY TO LIKE PULP ART?

- Know When To Fold 'Em

- Sketchbooks - why?

-

▼

June

(14)